1. A Cold Morning Arrival and Warm Welcome

Stepping out of the Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport, the chill in the Montréal air was biting but invigorating. The crisp wind cut through the layers of clothing like a reminder that this city, for all its urban charm, is shaped by the cold. The snowbanks lining the roads were starting to recede slightly, and the locals walked briskly, coats buttoned up tight, scarves snug against their faces.

The first thing that struck me wasn’t the weather but the scent in the air—a sweet, almost woody aroma, unmistakably maple. It lingered everywhere I went over the next few days. Whether it was from a passing food truck, a local café, or the steam rising from a boiling vat at a sugar shack, maple was inescapable. And rightly so. It’s more than a sweetener here—it’s a heritage.

2. The Essence of Maple: Visiting a Cabane à Sucre

The journey began with a visit to a traditional cabane à sucre (sugar shack) in the outskirts of Montréal, in the Laurentians region. The landscape shifted from cityscape to snow-laden forests, and soon, the unmistakable shape of a rustic wooden cabin came into view. Smoke coiled from its chimney, and a smell wafted through the air that was so enticing it was almost cinematic.

Inside, the cabane was warm and inviting. Long communal tables lined the hall, and the walls were hung with vintage tools and photographs that told stories of syrup seasons past. A robust Québécois man with a kind face offered us a tour. His hands were worn, calloused from decades of tapping trees and boiling sap. He led us to the evaporator, where fresh sap from sugar maples was bubbling vigorously.

It takes roughly 40 liters of sap to make just 1 liter of pure maple syrup. That ratio suddenly made every golden drop feel sacred.

After the tour, we sat down to a feast. Thick-cut bacon glazed in maple, baked beans, ham, eggs, and crêpes drenched in syrup—it was the kind of meal that settles deep into your soul. Then came the pièce de résistance: tire sur la neige, or maple taffy on snow. The process is simple. They pour boiling maple syrup onto a bed of fresh snow, then roll it onto a popsicle stick. It’s chewy, intensely sweet, and entirely addictive.

Before leaving, I bought a few bottles of syrup—amber, golden, and dark. Each has a distinct flavor, ranging from light and buttery to rich and almost smoky. They weren’t just souvenirs; they were little vials of memory.

3. A Discovery in Ice Wine

I had read about ice wine, but nothing could have prepared me for the first sip.

At a boutique liquor store in the Plateau Mont-Royal district, I came across a selection of wines tucked into a refrigerated section labeled “Vin de glace.” The shopkeeper, a passionate connoisseur with a deep knowledge of Québec viticulture, offered to host a tasting. He poured a tiny measure into a tulip-shaped glass. The wine, a golden amber, glistened in the light.

Ice wine is made from grapes that are left to freeze naturally on the vine. Harvested at precisely the right moment—often in the middle of the night in bitter cold—the grapes are pressed while frozen. The result is an intensely concentrated, sweet nectar that captures the essence of the fruit like nothing else.

The one I tasted was a Vidal Blanc from the Eastern Townships. It had flavors of apricot, honey, and ripe peach, balanced with just enough acidity to keep it from becoming cloying. I purchased two bottles on the spot. Back home, I imagined serving it with aged cheese or dessert. Or perhaps just sipping it slowly by candlelight, letting the memory of snowy Montréal unfold one drop at a time.

4. Artisan Markets: Treasures With a Soul

Wandering through Marché Jean-Talon, it’s easy to lose track of time. The market is partially covered in winter, but it’s still lively. Here, locals speak rapid French, bundled in layers as they select root vegetables, locally made cheeses, and sausages. But beyond the food, what drew my attention were the craft stalls set up along the market’s edges.

Handwoven wool scarves dyed with natural pigments. Pottery that was both rough-hewn and delicate, shaped by artisans who clearly knew their medium. One booth displayed hand-carved wooden spoons and cutting boards made from maple and cherrywood. The vendor, an older woman with keen eyes and a no-nonsense manner, explained the care that went into seasoning each piece.

She showed me a maplewood board infused with beeswax and oils, polished to a subtle sheen. I picked it up and felt its weight, imagined it on my kitchen counter, a tangible bridge between Montréal and my everyday life.

Another vendor offered hand-dipped candles scented with local herbs—fir, spruce, sage. I chose a pair, wrapped carefully in tissue, and felt a strange satisfaction knowing that these weren’t mass-produced. They bore the subtle imperfections of the human hand, each twist of wax and flick of color a signature.

5. A Walk Through Old Montréal: Heritage in Every Step

Strolling through Vieux-Montréal is like stepping into a French fairy tale. The narrow cobblestone streets, historic buildings, and gas lamps still flickering with real flame give the neighborhood a quiet, dignified charm. On Rue Saint-Paul, art galleries sit beside leather workshops, their windows displaying everything from intricate jewelry to hand-stitched journals.

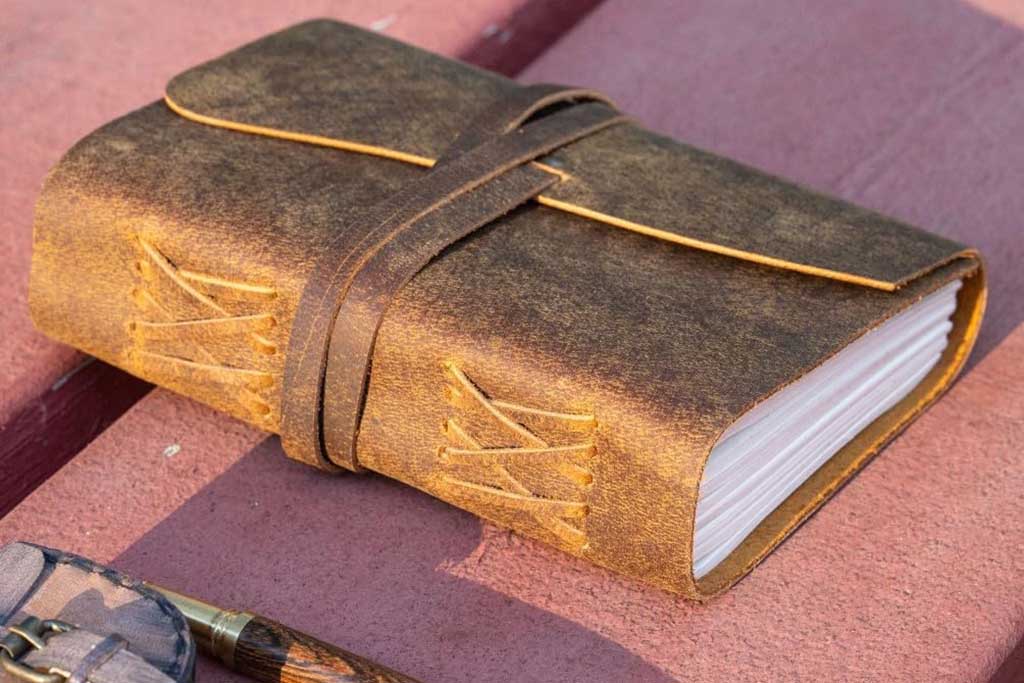

I ducked into a small boutique on Rue Saint-Vincent, drawn in by the display of leather-bound notebooks. Inside, I met a craftsman named Olivier who specialized in bookbinding. His hands moved with elegant precision as he stitched a spine. He spoke of the leather—sourced locally, tanned using old-world methods. He offered to personalize a journal for me, embossing my initials into the cover with a heated brass stamp.

An hour later, I walked out with the journal in hand. The leather was soft and smelled faintly of smoke and tannins. I hadn’t planned to buy a journal, but now I couldn’t imagine not having it. There was something timeless about the act of writing in such a book, as though each word carried more weight.

6. A Taste of the Unexpected: Local Chocolatiers and Soapmakers

On my second afternoon, I visited a chocolatier near Mile End. The shop’s interior was minimal—white walls, wood shelving, dim lighting. But the chocolates were works of art. Tiny squares with hand-painted tops, each filled with a different flavor: maple ganache, cranberry and ice wine reduction, smoked sea salt caramel.

The owner, a wiry man in his fifties, offered me a taste. “Try this one,” he said, placing a dark square into my palm. “Maple and whisky.”

It melted slowly on the tongue, revealing layers—first the bitterness of dark chocolate, then a wave of sweetness, then the warmth of whisky at the end. It was a masterclass in balance.

Just down the street, I found a soap atelier run by two sisters. Their soaps were molded like river stones, made with goat milk, shea butter, and essential oils from the boreal forest. I selected several—balsam fir, cedarwood, and a blend called “Neige de minuit” that reminded me of fresh snow and smoky chimneys.

They wrapped each one in waxed paper with a sprig of dried pine tucked inside. These weren’t just soaps. They were memories, preserved in scent.

7. The Unseen Value of Handcrafted Keepsakes

Each object I packed into my suitcase carried more than just weight—it carried a story. A bottle of syrup from a family-run sugar shack. A cutting board shaped by one woman’s hands in the market. A bottle of wine harvested at midnight under a veil of frost. A bar of soap that smelled like Montréal’s winter woods.

None of these things came from a factory. They weren’t wrapped in plastic or designed by committee. They came from people who live close to the land, who know the seasons and rhythms of their craft. That intimacy translated into the objects they made.

I realized something as I walked back to my hotel, my hands full of small parcels wrapped in brown paper and twine. These weren’t just souvenirs. They were tokens of connection. They represented not just Montréal, but a particular way of living—deliberate, seasonal, textured.